ANDY WARHOL, Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1

Similar Sale History

View More Items in ArtRelated Art

More Items in Art

View More

Item Details

Description

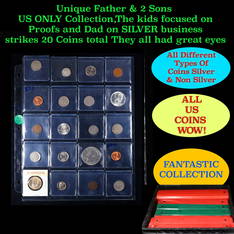

Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980

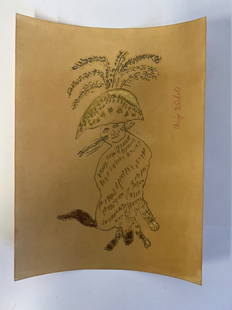

silkscreen and acrylic on canvas 54 1/8 x 41 3/4 in. (137.5 x 106 cm) Signed, titled and dated "Gold Marilyns, (Reversal Series), 1980, we see a familiar grouping of three identical images laid out in three equal rows. In Warhol's earlier work, we could clearly see the borders of each respective image, and, in doing so, we could mark the dimensions of each picture, as we see in Nine Marilyns, 1962. But in the present lot, Warhol's use of the negative denies us this precision in the horizontals — the cusps of Marilyn's hair seem to live directly above and below each other, giving us the illusion that three identical women posed for the same picture while standing next to each other. We cannot help but think of the widespread popularity of Marilyn Monroe during her own time; having completed nineteen films in four years, her omnipresence in the media seemed to suggest a supernatural multipresence in reality. Yet the picture as a whole evokes the notion of the many faces of Norma Jeane Baker; in the top right image's variations in saturation, we see the imperfections of Monroe's personal life, those that made her pour herself into her public persona. Alternatively, we see in the top left image only brilliant radiance of its exuberant gold, much as Monroe's celebrity existence hid the shortcomings of her private life. The visual impact of the present lot's silkscreened negative is haunting. Though she glares forward with the tempting grin of seduction, Marilyn Monroe's image has been reduced to shadows only. The area below her chin and cheekbones command the heaviest areas of Warhol's radiant gold, while the telltale signs of her vitality which Warhol chose to highlight in the early 60s—the red of her pouted lips and the unmatchable pink complexion of her cheek—have disappeared. It is as if the vivid figure of life over which the public wept has fled, leaving only her legend behind. It is no surprise that Monroe's façade in Nine Gold Marilyns resembles less that of a celebrity icon, and evokes more the immortal marble busts of classical Greece and Rome, and the sacred portraits of the Madonna. Warhol has chosen a suitable color for a goddess, one that recalls the golden splendor with which she graced the screen. In giving us an almost Classical impression of Marilyn Monroe, Warhol redefines the notion of screen idol. Monroe was, in fact, a symbol in which the American public placed their faith, a presence through whom they could live vicariously. In that way, rendering the star in gold is not only fitting but a study in the devotion of her adoring fans; many were not simply attracted to the star's beauty or entertainment value, but believed in her as a constant companion in their lives. Monroe's power to entice cult followers was itself worthy of making her a golden idol. Years before, in the early 1960s, Warhol's Factory operated under ideals of artistic radicalism—in its large scale production of artwork, the Factory experimented with divorcing the personal relationship of the artist from his work. In turn, there came to exist an indifferent production of art, one where art was a product rather than an existential accomplishment. It was in this mode that Warhol operated throughout the end of the 1960s and into the next decade. Yet in the Reversal Series, we see Warhol returning to the fundamental relationship between an artist and his work, even if the work in question is the artist's own history. In Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, Warhol is no longer alienated from the production of his work, for he revisits his earlier series. This revisitation rings of reminiscence, of an artist's nostalgic tie to the artist that he used to be. Therefore, the importance of Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, is in its self-referential origin. Rather than produce a single piece of Pop Art from a popular image in American culture, such as a celebrity, soup can, or politician, Warhol "referred to his own iconographic universe. He constructed the décor of himself, and, to renew its appearance, he only needed to cast a mirror-image of it (a reversal)" (G. Celant, SuperWarhol, Milan, 2003, p. 10). Consequently, the popular image of Nine Gold Marilyns, 1980 is not the image of Marilyn Monroe from "Niagara", but Warhol's own work from 1962. Taking into account Warhol's choice of subject, the present lot does not fall under the convenient category of Pop Art, for it is in a class of its own. In the same way that we frequently mirror our lives based on ideals taken from movies or other media, Warhol models his work on something equally unreal: his impression of Marilyn Monroe from nearly twenty years before. Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, in this state thrice divorced from reality, becomes very near what French philosopher Jean Baudrillard calls the "hyperreal" — something continually referenced but with no referents. Perhaps it is this hyperreality which is the logical end of Warhol's work: when all subjects of art continually refer to the past, it is our manners of reference which have value, not the objects to which they refer. Therefore, Pop Art's importance is not in its choice of subject, but in its manner of depiction. Pop Art's profound weight in philosophical matters makes it the continuation of a lineage begun with Duchamp's readymades. And, following Pop Art's lineage, we see it as the chief ancestor of conceptual art. The present lot becomes as much about its subject as it does the history of Andy Warhol's production of art. While he accomplishes the same end as he did in the 1962 Castelli show — reproducing Marilyn Monroe in death the same way that the public reproduced her in life—he also makes clear that his artistic process has advanced far beyond simple reproduction. In Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, we observe Warhol looking back on his extraordinary body of work, and recognizing it as a popular phenomenon itself. Warhol's multi-decade devotion to Monroe as a subject for his paintings is a testament to his deep appreciation for her in an aesthetic context; perhaps one reason that he chose to reproduce her image is that her beauty is a neverending source of inspiration. However, perhaps another is the similarity of Monroe to Warhol in a personal context; both Monroe and Warhol shared enormous talents of an artistic spirit, but what talents they offered often differed from what the public demanded. Monroe's desperate journey to shed her pinup image closely mirrors that of Warhol's drive to be the ultimate nonconformist. Though, ultimately, Monroe failed and Warhol succeeded, their ambitions to challenge our notions of normalcy unite them in Pop History. Yet, in its most straightforward interpretation, Warhol's elegant painting of Marilyn Monroe is poignant in its simplicity — it shows, in the most literal way, her golden age on the silver screen, and the indelible impression that she continues to make on the American consciousness.

Ο

silkscreen and acrylic on canvas 54 1/8 x 41 3/4 in. (137.5 x 106 cm) Signed, titled and dated "Gold Marilyns, (Reversal Series), 1980, we see a familiar grouping of three identical images laid out in three equal rows. In Warhol's earlier work, we could clearly see the borders of each respective image, and, in doing so, we could mark the dimensions of each picture, as we see in Nine Marilyns, 1962. But in the present lot, Warhol's use of the negative denies us this precision in the horizontals — the cusps of Marilyn's hair seem to live directly above and below each other, giving us the illusion that three identical women posed for the same picture while standing next to each other. We cannot help but think of the widespread popularity of Marilyn Monroe during her own time; having completed nineteen films in four years, her omnipresence in the media seemed to suggest a supernatural multipresence in reality. Yet the picture as a whole evokes the notion of the many faces of Norma Jeane Baker; in the top right image's variations in saturation, we see the imperfections of Monroe's personal life, those that made her pour herself into her public persona. Alternatively, we see in the top left image only brilliant radiance of its exuberant gold, much as Monroe's celebrity existence hid the shortcomings of her private life. The visual impact of the present lot's silkscreened negative is haunting. Though she glares forward with the tempting grin of seduction, Marilyn Monroe's image has been reduced to shadows only. The area below her chin and cheekbones command the heaviest areas of Warhol's radiant gold, while the telltale signs of her vitality which Warhol chose to highlight in the early 60s—the red of her pouted lips and the unmatchable pink complexion of her cheek—have disappeared. It is as if the vivid figure of life over which the public wept has fled, leaving only her legend behind. It is no surprise that Monroe's façade in Nine Gold Marilyns resembles less that of a celebrity icon, and evokes more the immortal marble busts of classical Greece and Rome, and the sacred portraits of the Madonna. Warhol has chosen a suitable color for a goddess, one that recalls the golden splendor with which she graced the screen. In giving us an almost Classical impression of Marilyn Monroe, Warhol redefines the notion of screen idol. Monroe was, in fact, a symbol in which the American public placed their faith, a presence through whom they could live vicariously. In that way, rendering the star in gold is not only fitting but a study in the devotion of her adoring fans; many were not simply attracted to the star's beauty or entertainment value, but believed in her as a constant companion in their lives. Monroe's power to entice cult followers was itself worthy of making her a golden idol. Years before, in the early 1960s, Warhol's Factory operated under ideals of artistic radicalism—in its large scale production of artwork, the Factory experimented with divorcing the personal relationship of the artist from his work. In turn, there came to exist an indifferent production of art, one where art was a product rather than an existential accomplishment. It was in this mode that Warhol operated throughout the end of the 1960s and into the next decade. Yet in the Reversal Series, we see Warhol returning to the fundamental relationship between an artist and his work, even if the work in question is the artist's own history. In Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, Warhol is no longer alienated from the production of his work, for he revisits his earlier series. This revisitation rings of reminiscence, of an artist's nostalgic tie to the artist that he used to be. Therefore, the importance of Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, is in its self-referential origin. Rather than produce a single piece of Pop Art from a popular image in American culture, such as a celebrity, soup can, or politician, Warhol "referred to his own iconographic universe. He constructed the décor of himself, and, to renew its appearance, he only needed to cast a mirror-image of it (a reversal)" (G. Celant, SuperWarhol, Milan, 2003, p. 10). Consequently, the popular image of Nine Gold Marilyns, 1980 is not the image of Marilyn Monroe from "Niagara", but Warhol's own work from 1962. Taking into account Warhol's choice of subject, the present lot does not fall under the convenient category of Pop Art, for it is in a class of its own. In the same way that we frequently mirror our lives based on ideals taken from movies or other media, Warhol models his work on something equally unreal: his impression of Marilyn Monroe from nearly twenty years before. Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, in this state thrice divorced from reality, becomes very near what French philosopher Jean Baudrillard calls the "hyperreal" — something continually referenced but with no referents. Perhaps it is this hyperreality which is the logical end of Warhol's work: when all subjects of art continually refer to the past, it is our manners of reference which have value, not the objects to which they refer. Therefore, Pop Art's importance is not in its choice of subject, but in its manner of depiction. Pop Art's profound weight in philosophical matters makes it the continuation of a lineage begun with Duchamp's readymades. And, following Pop Art's lineage, we see it as the chief ancestor of conceptual art. The present lot becomes as much about its subject as it does the history of Andy Warhol's production of art. While he accomplishes the same end as he did in the 1962 Castelli show — reproducing Marilyn Monroe in death the same way that the public reproduced her in life—he also makes clear that his artistic process has advanced far beyond simple reproduction. In Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1980, we observe Warhol looking back on his extraordinary body of work, and recognizing it as a popular phenomenon itself. Warhol's multi-decade devotion to Monroe as a subject for his paintings is a testament to his deep appreciation for her in an aesthetic context; perhaps one reason that he chose to reproduce her image is that her beauty is a neverending source of inspiration. However, perhaps another is the similarity of Monroe to Warhol in a personal context; both Monroe and Warhol shared enormous talents of an artistic spirit, but what talents they offered often differed from what the public demanded. Monroe's desperate journey to shed her pinup image closely mirrors that of Warhol's drive to be the ultimate nonconformist. Though, ultimately, Monroe failed and Warhol succeeded, their ambitions to challenge our notions of normalcy unite them in Pop History. Yet, in its most straightforward interpretation, Warhol's elegant painting of Marilyn Monroe is poignant in its simplicity — it shows, in the most literal way, her golden age on the silver screen, and the indelible impression that she continues to make on the American consciousness.

Ο

Buyer's Premium

- 25% up to $50,000.00

- 20% up to $1,000,000.00

- 12% above $1,000,000.00

ANDY WARHOL, Nine Gold Marilyns (Reversal Series), 1

Estimate $7,000,000 - $10,000,000

7 bidders are watching this item.

Shipping & Pickup Options

Item located in New York, NY, usSee Policy for Shipping

Payment

Related Searches

TOP