CRYSTAL RIVER, Fla. – I spend a lot of time answering readers’ questions about their furniture. I love to do it and it sure beats working for a living. I sit at my computer, amid my research library, and sort out the details of periods and styles, of hardware and glass, of origins and histories and mysteries. I get to rummage back through thousands of photographs I took in my restoration shop and the additional thousands I have taken since then. This sometimes helps me remember a tidbit or clue about a piece or a style or a period.

I generally try to show the reader how to determine some facts about a particular piece of furniture using a set of clues that becomes almost second nature to the experienced furniture sleuth. I have written on occasion that the greatest blessing in an antique is a solid provenance, an indisputable history of the piece verified by a source other than oral family tradition. Such sources could be a will, a bill of sale, a probate list or a bankruptcy inventory.

The second greatest blessing would be a signature, preferably that of the maker. That of an owner from over 100 years ago can give a solid lead on where and when that piece came from. But even that, like so many other things about furniture identification, can, on occasion, become ambiguous, leading to more questions than it answers. Here is an example I ran into some years ago.

A good customer pulled into my shop with what appeared to be a genuine “train wreck” in the back of his pickup. I told him I hoped he hadn’t paid real American money for that thing. It was a mid-19th century Rococo marble-top dresser, walnut with burl on the three-drawer panels. The glistening white marble was intact but that was about the extent of it. The case was listing heavily to port, with gaps showing between the rails and stiles. The three drawers showed only the outline of the carved fruit pulls that had once been there. The finish was a myth. In short I told him he had better like this piece because it was going to cost a bundle to restore – probably more than it was worth.

Then came the inevitable family story. (There’s that oral tradition thing again.) The piece came from an old building in New York that was about to be torn down. My customer, then in the bloom of middle age, had spent his summers as a child in the building with his grandmother. The furniture had originally belonged to her grandmother and the dresser had been in his summer room so I figured he was probably going to spend the money – just tell him how much.

I had to survey the piece to get him in the ball park so I decided to start right there on the truck before we even unloaded it – just in case. The top drawer was jammed tight against the stile. I was able to pull it out as it fell apart in my hands. The second drawer was a little harder to remove but it was worth the effort because inside the drawer were the six missing pulls and the original casters. Things were looking up. The third drawer surrendered without a fight.

Having been around the trade for a couple of years, I knew that the bottom kick panel probably concealed another drawer. But it sure didn’t feel like a drawer when I tried it, and my customer was aghast when I put some force on it. When the drawer finally opened, his jaw dropped. In all the summers he had lived out of that dresser he had never known about the fourth drawer. Small wonder. For some reason the drawer was wedged shut with wooden shims. Somebody didn’t want that drawer open. Why? No idea. It was empty and had been for years. Maybe it was just to keep the kid from hiding something.

As I continued my survey it was obvious that each drawer would have to be totally disassembled and reglued. As each drawer was disassembled, the badly worn sides would have to be repaired. The case was in even worse shape than the drawers and it too would have to be disassembled and reglued.

The drawer runners inside the case were also in sorry shape. As with many pieces of that era, the inside runners consisted simply of a piece of square poplar stock nailed into the frame, front and rear, using rectangular headed cut nails, with no supporting glue blocks. The square stock was nailed flush to the front rail and followed a scribed line to the rear of the case. When these inside runners are worn and grooved to the point of impeding the drawer’s progress, the standard fix is to carefully remove the runner from the case, turn it over so the grooved side is down and the flat side is up and, using the original nails, reinstall the runner along the scribed line. Of course, if someone has already beaten you to this trick, new runners must be made and installed. In this case it appeared that no one had ever worked on the inside runners so I was able to turn them over.

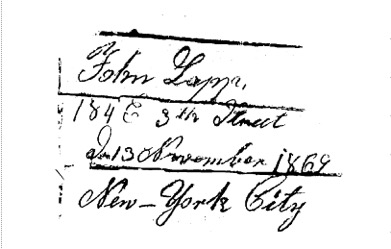

After agreeing on a price the work began. Starting at the top, I worked my way down each side of the case, removing each inside runner, turning it over and carefully reinstalling it with the old nails. The first and second drawer runners were inverted and reinstalled without incident. Then I carefully removed the third runner and noticed an odd bit of color where it had been. A close look showed a cavity in the wood that had been concealed by the runner. And there was a piece of paper in the cavity! After careful removal, the paper turned out to be old, blue figured paper, folded in thirds. Upon unfolding the paper, 19th century flowing hand script presented itself. According to an expert in 19th century handwriting it said:

John Lay Jr.

184 E 3th Street

On 13 November, 1869

New York City

Since no one had removed that inside runner since the day it was put in place, I can only conclude that John or someone on his behalf put it there. Did John make the piece? Or did John commission the piece? The name “John Lay Jr.” did not have a place in the owner’s family history that he knew of. Maybe he was a famous cabinetmaker so I started to search.

I tried the usual sources, E.H. Bjerkoe’s book The Cabinetmakers of America and William Ketchum’s American Cabinetmakers, Marked American Furniture, 1640 –1940 to no avail. So maybe he wasn’t famous. Still there had to be a record of him. New York has excellent census records from that period, so I worked there.

In the 1870 census I found two people named John Lay. One was a 50-year-old store clerk, an unlikely maker or owner of this cabinet. But the other was a young German immigrant, age 29, living with his wife and two young daughters in the 16th District, 11th Ward of New York City. His occupation? Cabinetmaker! And modern maps show that 184 E. 3th (sic) Street is only a couple of blocks outside the old 11th Ward. Mystery solved? Maybe not.

There are a couple of problems with such a quick solution besides the fact that it was too easy, in spite of Occam’s Razor theorem that says the simple solution is usually the best. First there is the problem of language and spelling. The name Lay is generally assumed to be of Germanic extraction. In German, apparently the pronunciation of “Lay” very closely approximated “Loy” in English and some apparently tried to preserve the Old Country sound by adopting the spelling “Loy.” That opened up another broad avenue of inquiry since Loy was also an Irish surname used in 19th century New York.

In the 1870 census the name John Loy appeared in the 20th Ward, west of Sixth Avenue between West 26th Street and West 40th Street. This 46-year-old man had his occupation listed as “moulder/wood” and his place of birth as Ireland. He apparently had moved to the 20th Ward from the 22nd where he was shown in 1860 and listed as a “sawyear” – not necessarily a cabinetmaker but surely a woodworker. And he had a son named John (a “Jr.” perhaps?) who was 8 years old in 1860 but who would have been 17 nine years later in 1869 when the note was penned. His occupation was listed as “apprentice carpenter” in 1870. Was it his youthful hand, tired from a day of making drawer runners, that signed an “o” in Loy that looked like an “a” on the original paper?

Then there was the John Loy listed in the 1869–1870 New York City Rivers Directory as having a cabinet shop at 126 Amity St. and living at 90 Sixth Ave. But Amity is no longer a street, so where was 126 Amity? Because Amity was changed to West Third Street just before 1900, according to the New-York Historical Society, it appears Mr. Loy had a shop just off Broadway near Washington Square. That’s not too far from the address on the handwritten scrap but is certainly not the same. A satellite workshop perhaps or another shifting of street names and numbers?

I never solved the puzzle completely. This just helps to remind us that antiques are full of surprises and even when we are given the gift of a signature and a date, things are not always perfectly clear.

___

By FRED TAYLOR

Send comments, questions and pictures to Fred Taylor at P.O. Box 215, Crystal River, FL 34423 or email them to him at info@furnituredetective.com. Visit Fred’s newly redesigned website at www.furnituredetective.com and check out the new downloadable “Common Sense Antiques” columns in .pdf format.

His book “How To Be a Furniture Detective” is available for $18.95 plus $3 shipping. Send check or money order for $21.95 to Fred Taylor, P.O. Box 215, Crystal River, FL, 34423.

Fred and Gail Taylor’s DVD, “Identification of Older & Antique Furniture” ($17 + $3 S&H) is also available at the same address. For more information call 800-387-6377 (9 a.m.-4 p.m. Eastern, M-F only), fax 352-563-2916, or info@furnituredetective.com. All items are also available directly from his website.