LONDON – The boy couldn’t care less – his attitude is ‘why buy antiques when you can buy new for less money?’

Interestingly, however, the older of our two young apprentices has started collecting and, yes, we were amazed too. The bug bit after she purchased her first home: a cozy little flat in a grand Georgian townhouse, the walls and shelves of which were crying out to be covered with collectors’ items.

First off, she begged her mother’s 1950s handkerchief glasses, each one now doing service as candlelit fairy lights. Then she decided to hang the wall over what was once a fireplace with ’50s mirrors – you remember the ones: fancy shield-shaped jobs with beveled glass and chains to hang them from the picture rail. There were six hanging there in precarious symmetrical precision last time we visited.

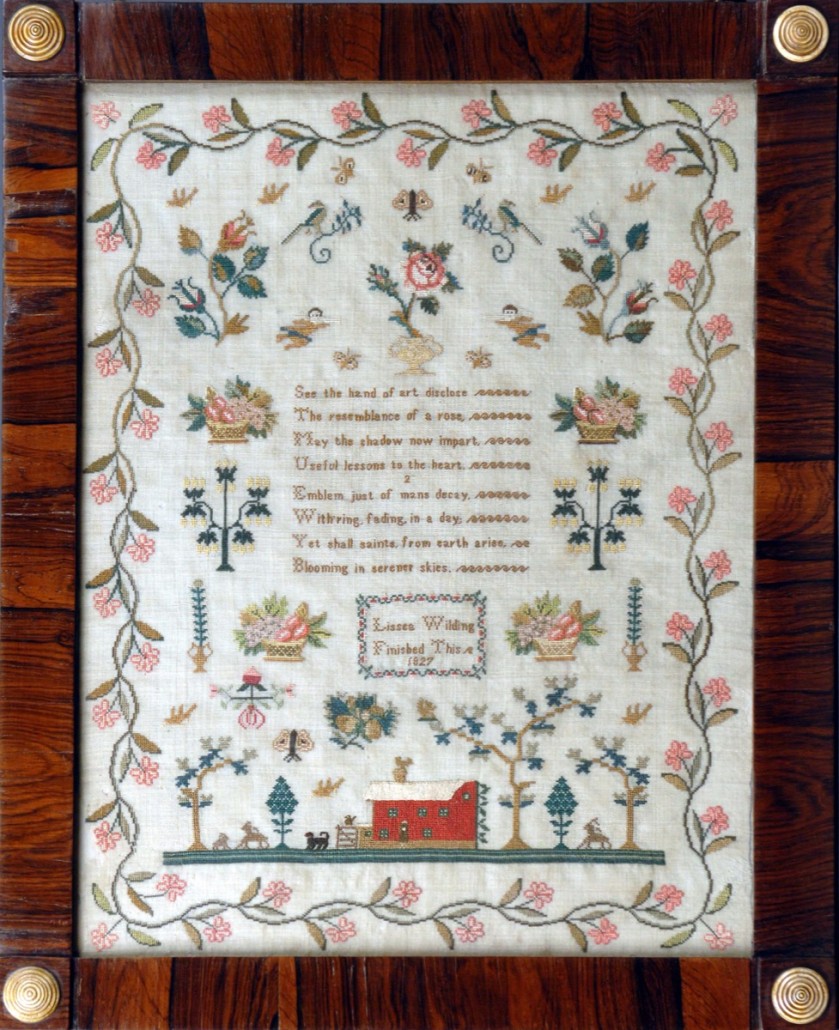

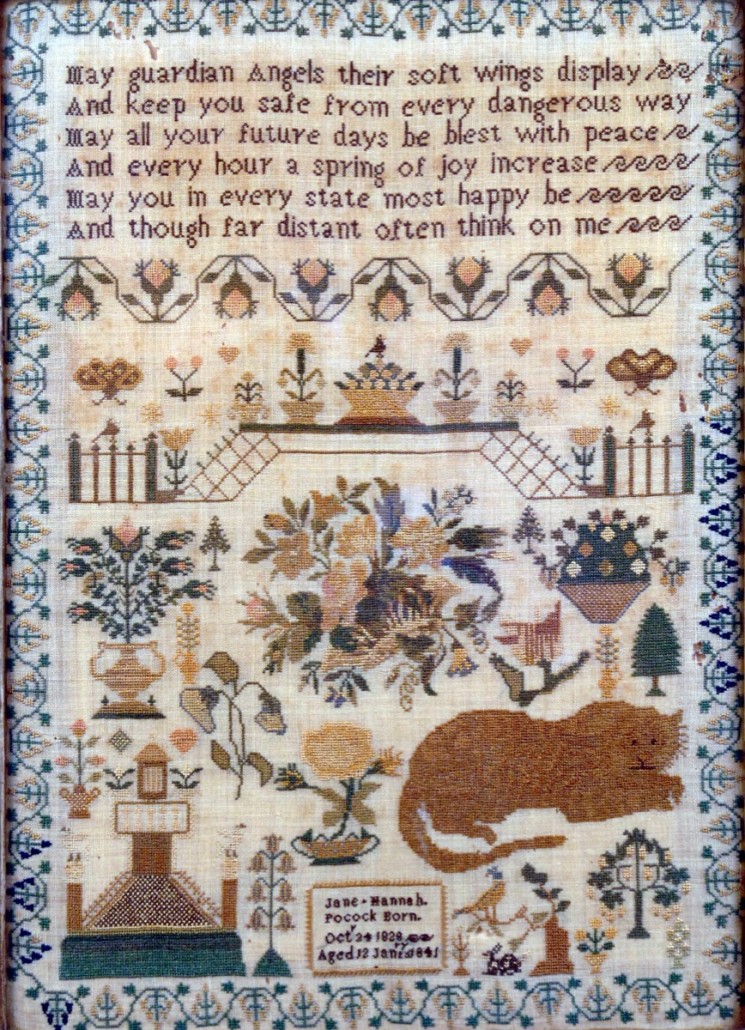

Now she’s announced she wants a Victorian embroidered sampler from her mother’s collection. We’ve told her to dream on and find her own. What it might cost her is open to many factors, but in general terms, they are getting more sought after and, like most things, they are getting more expensive. Fortunately, they haven’t got quite so out of reach as in America, where folk art in general and samplers in particular are much more highly prized and priced.

Prices were stoked in 2011 when Sotheby’s New York sold the landmark Betty Ring collection of schoolgirl embroideries. It raised a staggering $4.4 million and set a record for a single sampler (below) by Mary Antrim, of Burlington County, dated 1807. It sold for $1,070,500 (£665,000).

Worked in silk and painted paper on linen, the view of livestock, picket fences and clapboarded farm buildings had been exhibited at the American Museum of Folk Art. According to its purchaser, a dealer bidding on behalf of a private collector, it “transcends the world of needlework. It stood out in a unique way as a folk art statement.”

Sadly, or perhaps fortunately, the same enthusiasm has not reached our shores yet for what I believe are our unique social history documentaries of children’s education in the 19th century. Otherwise few could afford them.

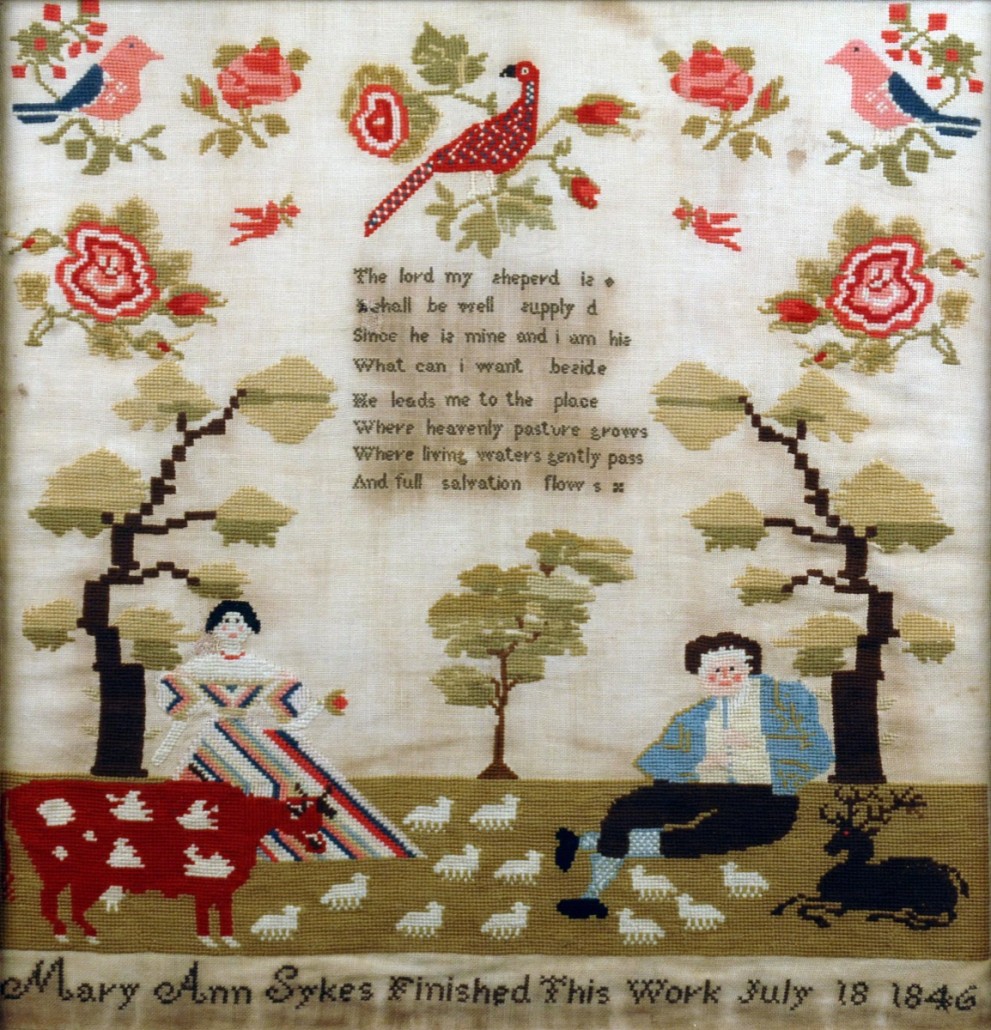

In the 16th century, samplers were a method of recording the different stitches and designs available for fashionable clothing and furnishings at a time when books were rare and expensive. Generally, early examples were long – up to a yard – narrow strips of material, usually a coarse linen, that was stored rolled around an ivory rod.

Into the strip was worked row after row of different stitches that served a purpose similar to a pattern book. New styles were added as they appeared, so that by the time the length of the strip was filled, it was a valuable record that represented several years’ work.

Clearly these early samplers, or samplaires as the French called them, were highly valued even then. They often figure in inventories of the contents of large houses and in the wills of the people who lived in them. Happily too, a good number of them have survived until today, long after the clothes that bore the designs were discarded.

By the later years of the 17th century, fashion was under the austere grip of the Puritans, but still the sampler survived. No one was more aware of the importance of girls being trained as competent needlewomen as they were and so the sampler developed a role as a “textbook.” Now, instead of long thin lengths of material, shapes changed to becoming more square or oblong. In addition, with the growth of education and schooling, the sampler became the place for children to learn their alphabet and numbers and receive their religious and artistic education.

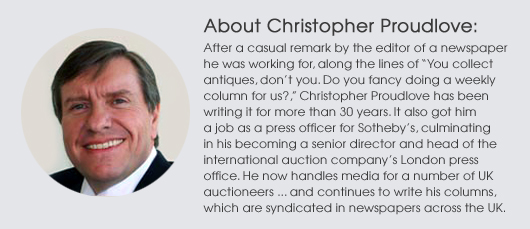

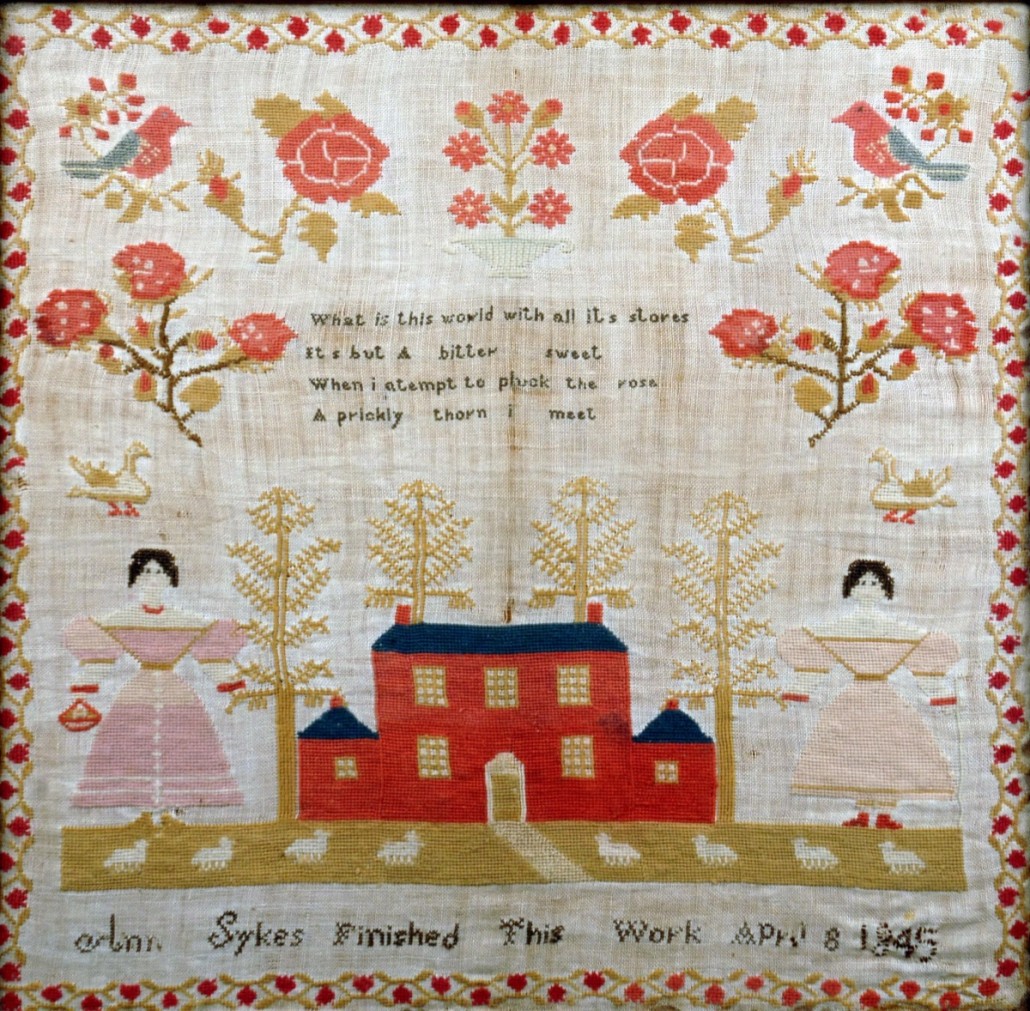

The advent of the 18th century confirmed the importance of the sampler in the education of children. Needle and thread were as important as chalk and writing slate for pupils often at the tenderest of ages. Reading skills started with simple ABC lettering, followed by prosaic verses. Arithmetic lessons enabled pupils to calculate the positions in which to start decorative borders and patterns; religious training was provided when verses adopted moral overtones and when samplers began to carry embroidered pictures of houses, figures and animals such as deer, lions, sheep and birds, the educational virtues of the art form was complete.

By now, materials in use had been refined. Background material was generally silk, as was the thread used for the actual stitch work. Stitch size remained small and delicate, and children – both boys and girls – were encouraged to apply their names, ages and the date on which a piece of work was completed. This latter feature is a source of much joy to the collector. Clearly, a dated sampler leaves no doubt when it comes to fathoming out the period from which a particular example comes and prices rise accordingly.

Rarer inscriptions give the dates on which work was started and finished, often two or three years later. Similarly, with a lot of luck, separate examples can be found bearing the names of different children in the same family. Often an auction sale of the contents of a single house is a source of the latter. Samplers also turn up that contain spelling mistakes, while others are obviously unfinished. Studies of the verses and rhyming couplets featured on samplers is a source of interest and amusement.

The 19th century saw a general decline of sampler art. The canvas on which they were worked became coarser and the colored silks were substituted by cheaper wools. Virtually all 19th-century samplers include an inscription of some sort. Earlier examples also often have a house surrounded by a garden with fence, occasional trees, flowers and animals, with the sky area used for the verse of around four lines, the name and age of the embroiderer and the date.

Later examples are minus their pictorial motifs and instead one finds rigid lines of poor attempts at decoration using cross-stitched zigzag lines, together with verses with a Biblical context and pious poems on the duty of children to their parents.

However, the unique nature of a sampler makes them eminently collectible and their addition to a display of pictures, for they are all usually well framed in woods such as maple, mahogany and rosewood, make them a fascinating insight into schooldays of an earlier era.

___

By CHRISTOPHER PROUDLOVE